MA Swings an Ax at Drug Prices

- The Wall Street Journal

- By Laura Johannes

Massachusetts in organizing an assault on prescription drug prices — and pharmaceutical companies are up in arms.

With a little-noted provision, inserted into budget legislation in the waning hours of deliberations last month, the state passed a measure that could sharply cut medicine prices for 1.5 million of its citizens.

The unique plan authorizes a bundling of a number of groups — state employees, people on Medicaid and state aid, and those who lack prescription drug coverage — into a vast pool with enough clout to command discounts on prescriptions.

It’s one of the broadest government moves to aid people who don’t have health insurance. And the plan, which will cover about a quarter of the state’s population, could serve as a model for a national program, advocates say. About 70 million Americans lack drug coverage.

Purchasing for the new pool will be handled by a state-appointed pharmacy benefits manager, similar to those that work for health-maintenance organizations and other insurers to bargain with the drug companies and pharmacies.

The law, which faces some hurdles, stands to save state taxpayers and patients, many of them elderly or indigent, and about $170 million a year, estimates former U.S. Rep. Joseph Kennedy. The provision came at his initiation; his uncle, U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy, proposed a similar, ultimately unsuccessful federal measure earlier this year to cover Medicare recipients.

Joseph Kennedy is chairman of the Citizens Energy Corp., a Massachusetts nonprofit group that, despite its name, has brokered pharmacy-benefits before. He says he hopes Citizens Energy will be chosen to play a major role in running the program.

The measure’s zip through the legislature gave opponents little time to react. Drug companies, drugstores and others argue the whole thing is a thinly veiled move toward government price controls. Merck & Co., the Genetics Institute Unit of American Home Products Corp., Biogen Inc., Genzyme Corp. and Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc. all wrote letters, in vain, seeking a gubernatorial veto.

Merck owns a unit that is one of a handful of pharmacy benefits managers already working for plans covering the state’s 255,000 employees, retirees and their dependents. In its letter to Gov. Paul Cellucci, Merck said the price controls that would stem from the law “have repeatedly been shown to stifle innovation and the discovery of new technology.” In his protest letter, Jim Vincent, Biogen’s chief executive, said the program will “send the message that Massachusetts is an antibiotechnology and antipharmaceutical industry” state.

Under the Massachusetts law, the state will contract with a nonprofit group to develop and manage the program. The uninsured members of the buying pool, who would still pay for their own medications but at state-negotiated discounts, include 500,000 people without any insurance and about 300,000 seniors on Medicare without drug benefits, Mr. Kennedy says.

The law strikes at the heart of a bizarre side effect of managed care: As HMOs and government payers have increasingly won deep discounts on medicines, the drug companies and pharmacies have made up some of the difference by charging full price to everyone else — mainly the elderly and uninsured. “It is hard to justify charging just the poorest and most vulnerable people in our society the most money for a basic necessity of life,” Mr. Kennedy says.

In a recent survey, the advocacy group Public Citizen found that seniors paying out-of-pocket for drugs in New York state paid more than double the government price. And Express Scripts Inc., a large pharmacy-benefits manager in Maryland Heights, Mo., estimates that cash-and-carry customers typically pay 20% to 25% more than the price managed-care plans are able to negotiate.

But pharmacies, especially independents, can ill afford further discounts, says the Retailers Association of Massachusetts. The group of 1,700 retailers also fears that pharmaceutical companies will sock its members, among others, with price hikes to recover any reductions they suffer from the new program.

Spending on pharmaceuticals, spurred partly by expensive new medicines, rose an estimated 17% over last year, says Fred Teitelbaum, Express Scripts’ Vice president of research. That walloped employers who foot the health-insurance bills — and fattened bottom lines at pharmaceutical companies.

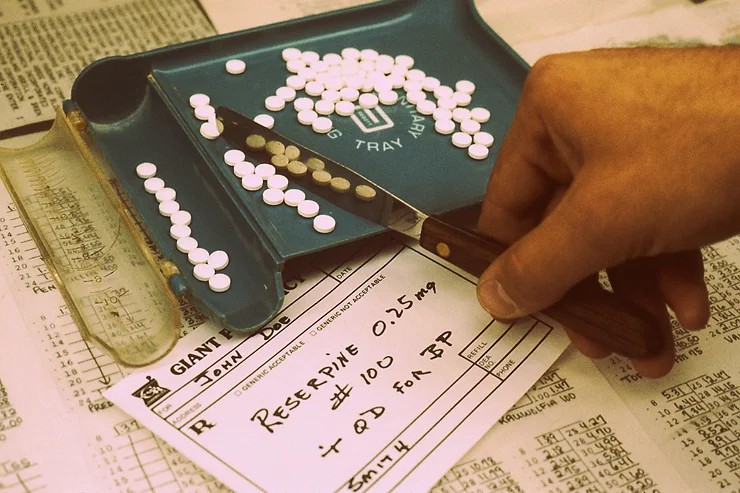

Pharmacy benefits managers, widely used in the private sector, typically work for HMOs to negotiate for bulk purchases of drugs at steep discounts. They often restrict coverage to a list of approved drugs, called a formulary. With it, they force manufacturers to discount their prices if they want their medications included on the list.

While a formulary would give the Massachusetts program similar clout, it isn’t clear whether the state appointed manager will be allowed to establish one. The budget provision says only that the manager must maximize savings “without reducing the quality of prescription drug benefits, if any.”

But some patient groups worry a formulary would inappropriately limit choices for medicines. “This whole thing seems to be putting government between patients and their physicians, and that’s very troubling,” says Carl Dixon, executive director of the Kidney Cancer Association, in Evanston, Ill.

Andrew Natsios, the Massachusetts secretary of administration and finance, has until mid-January to develop the new program, which includes preparing a request for proposals for a nonprofit group to run it. A spokesman for Mr. Natsios, one of the governor’s chief lieutenant, said the state is assembling a team to work on the program.

“In theory, it’s a great idea,” says the spokesman, Joseph Landolfi. “But how feasible is it? Can it in fact be done? That’s what we’re going to look into.”

After he reviews proposals and holds a public hearing, Mr. Natsios is authorized to scrap the idea altogether if he finds it doesn’t save taxpayers money or provide “other substantial public benefits.”

Mr. Kennedy, who hopes the program will proceed, started Citizens Energy in the 1970s to procure low-cost heating oil for needy Massachusetts residents. It later helped start the state’s pharmacy-benefits management craze through a joint venture with Medco Containment Services, which Merck later bought.

Several Citizens Energy executives — in but not Mr. Kennedy, who was then in Congress — benefited handsomely from Medco stock options received as part of their compensation several years ago. Citizens Energy has said its executives did nothing wrong by accepting the options.

As for the new law, Citizens Energy says that if it has any influence in the choice of a benefits manager, Merck-Medco would get no special favors.